III. The Early Years(1931 – 1935)

The camera as a lightning quick brushFor Cartier-Bresson, the 1930s not only mark the beginning of his career as a celebrated photographer, they are also the most creative years in his life. It is amazing that many of his most famous pictures date from his period as a newbie. As mentioned earlier, Cartier-Bresson's real preference was set for drawing, but still he got famous for his photographs. Should his choice for photography then be regarded as an inferior alternative to drawing, only made to reach more people? Not really, as he applies his extended classical training as a painter extendedly while shooting. He can reap the benefits of his numerous visits to museums and galleries: with a slight bend of the knee or a rotation of the head, he determines the perspective, just like a painter, while his trained eye is able to quickly recognize geometric shapes and harmony in his images. He considers his Leica merely to be an « advanced pencil », with the difference that the « drawing » he has in mind, is immortalized in a fraction of a second. Note that Cartier-Bresson almost didn't care about the technical aspect of photography, such as developing. |

|||

FIG.7 Ghetto, H. Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos Warsaw, Poland, 1931 |

|||

|

Between 1931 and 1935 Henri Cartier-Bresson travels through Eastern Europe, Spain, Italy and Mexico along with his friend and writer André Pieyre de Mandiargues. When he visits a country, he deliberately chooses to stay there for several months, living among the poor. Without a predefined goal, Cartier-Bresson froths the streets and photographs — intuitively — everyday life, as if he is drawing in a sketchbook. During these journeys, he is confronted with various social abuses, something that clearly shines through in his first set of pictures from Eastern Europe (FIG.7). |

|||

“I find that you have to blend in like a fish in water, you have to forget yourself, you have to take your time, that's what I reproach our era for not doing.”Henri Cartier-Bresson

|

|||

|

Lots of the best pictures he realizes in this period are later included in Cartier-Bresson's first book, Images à la Sauvette. Thus, the idea of le moment décisif is already present in his work from the beginning. However, we can distinguish between the photos from the interbellum and his postwar work. As previously quoted, in the former period Cartier-Bresson was influenced by certain elements of surrealism. His first — very typical — photos therefore nearly all share a common feature: the suggestion of something greater. He composes his images in such a way that they imply a deeper meaning to the viewer. Le moment décisif here serves as a scalpel that cuts a visual fragment with unprecedented precision from its context and envisions a captivating higher reality in a seemingly commonplace picture. |

|||

FIG.8 H. Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos Valencia, Spain, 1933 |

|||

|

One of the clearest examples hereof is the shot in which a boy is gazing towards the sky in a weird-looking trance-like way. In the background, a dramatic weather-beaten wall is visible (FIG.8). In reality, the boy is just eye-tracking the ball he threw in the air, but by clicking at this very moment and leaving the ball out of sight, Cartier-Bresson sets us to dream about a deeper, surreal meaning. Unlike some self-proclaimed followers, his work generally remains rich in content and he doesn't lapse into a superficial game of misleading framing. Although a photographer is in principle limited in his subjects, here he almost sculpts his own image, forcing his will upon reality. The second interpretation of le moment décisif, after World War II, is actually doing just the opposite. The precise choice of pushing the button now gives us more background information on the photo. You can read more about Cartier-Bresson's Images à la Sauvette in the chapter about The Decisive Moment. |

|||

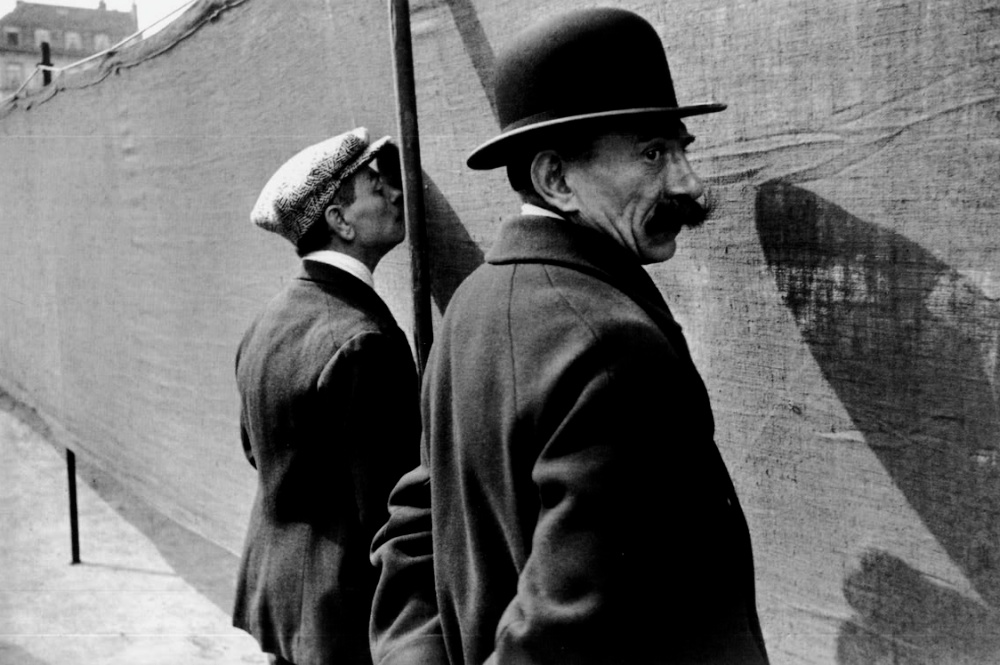

FIG.9 H. Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos Brussels, Belgium, 1932 |

|||

|

Another great shot with a surreal touch is the photo of two gentlemen — one quasi sniffing, the other suspiciously looking backwards — who are standing in front of a fence (FIG.9). It requires some study before the viewer realizes that the two men are trying to follow a match through the canvas. Then we see a nice contrast between the farthest man, who is trying to capture a glimpse of whatever is happening on the other side in a strange and unabashed pose, and the man with the well-lined trench coat, bowler hat and mustache, who seeks to preserve his dignity. He turns his head slightly toward the photographer and watches him closely from the corner of his eyes. The spy being spied on. |

|||

FIG.10 H. Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos Asilah, Morocco, 1933 |

|||

|

Cartier-Bresson also knows like no other how to make geometrically perfectly balanced images, in which the human expression is replaced by graceful figures from nature, in perfect harmony with their environment (FIG.10). In 1934 Cartier-Bresson spends a year in Mexico, where he fully exploits his experience — from his training as a painter to the many hours wandering through cities, in search of a catchy image — and takes some of his most original pictures (FIG.11). In Mexico, he also gets the nickname « bel homme au visage couleur de crevette ». |

|||

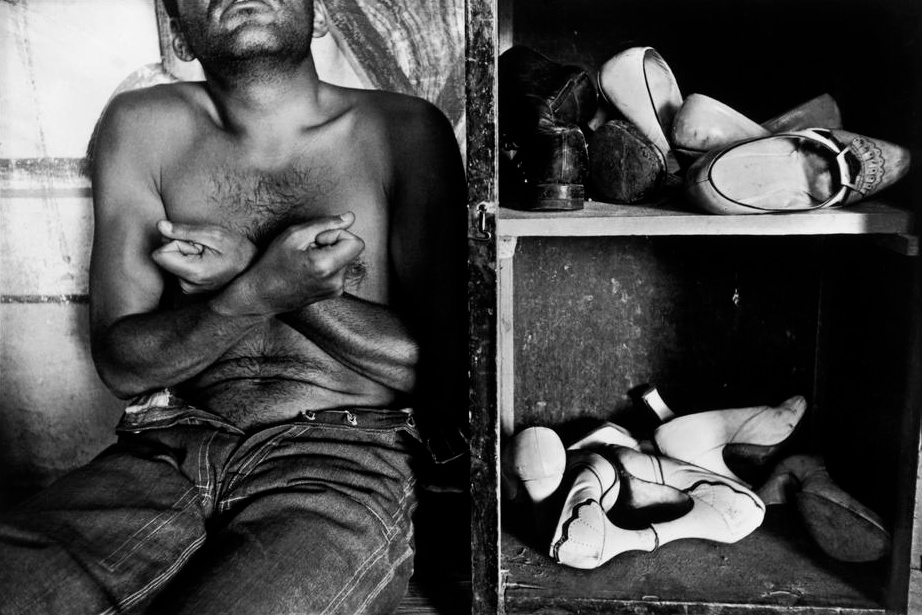

FIG.11 H. Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos Santa Clara, Mexico, 1934 |

|||

|

In 1933, the first exhibition devoted entirely to Cartier-Bresson is organized in Madrid. Then, in 1934, he has an exhibition in Mexico City, which is moved to the Julien Levy Gallery in New York in 1935. The international breakthrough is a fact. { Printer-friendly version } { Read on: To International Fame (1935 – 1952) } |

|||

|

Le Couperet HCB © Frederik Neirynck 2004 – 2024

|

|||