II. Influences(1925 – 1931)

From Buddhism to SurrealismIn 1927, after leaving the Lycée Condercet, Henri Cartier-Bresson goes to the studio of André Lhote (1885 – 1962), an admired pedagogue but less talented painter, where he learns about the basic principles of composition and perspective. Here, Cartier-Bresson stated afterwards, he learned to "read and write". Lhote takes his pupils to the Louvre and other galleries to study both classical and contemporary art. In addition to modern art, Henri Cartier-Bresson is also captivated by Renaissance painters such as Piero della Francesca and Jan van Eyck. Meanwhile, he extends his library with publications of Freud and Marx. When Cartier-Bresson meets his old teacher again, shortly before his death in 1962, Lhote attributes the success of his photos to the training with him in art painting. Despite the hint of arrogance, it is a theorem which beholds a lot of truth and it is a merit where Andre Lhote can genuinely be proud of. |

|||

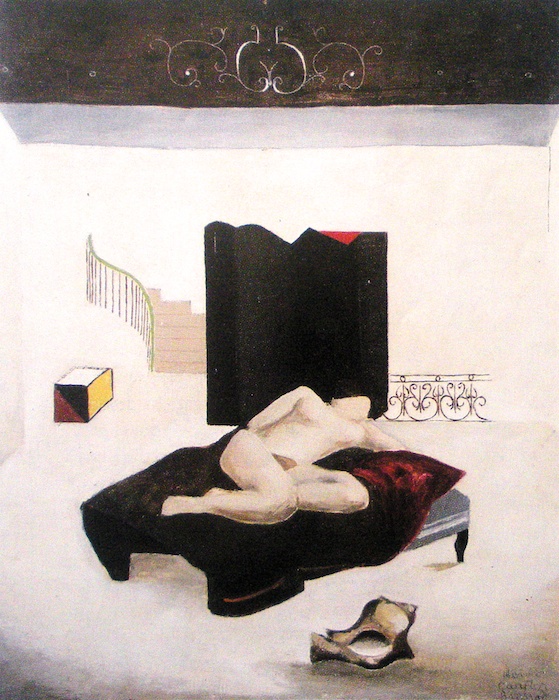

FIG.4 Studio of André Lhote, H. Cartier-Bresson France, 1927 |

|||

|

Still, Henri Cartier-Bresson has difficulties with the overload of rules in Lhote's style. Moreover, in 1925 the youthful Cartier-Bresson had already acquainted with the Surrealism that manifested in Paris from the beginning of the 1920s. He is particularly fascinated by the ideas of André Breton (1956 – 1966). He regularly attends the meetings of the Surrealists at the Café Cyrano in the Place Blanche. As a 17-year-old adolescent, he listens to the heated discussions that Breton has with his allies and opponents. Therefore, it are not really the Surrealist painters who leave a mark on Cartier-Bresson, but rather the Surrealist viewpoints on the importance of spontaneous expression and intuition (not luck or chance), and their rebellious lifestyle. Disappointed with his achievements as a painter, he destroys most of his paintings after a few years. The paintings that remain are quite well done but lack an artistic individuality (FIG.4). Dissatisfied with the impotence to change the world — if only a little — with his paintings and in an attempt to return to himself, he leaves for Africa in 1931, after having spent a brief period in Cambridge. He goes hunting, not for images but for animals. As a matter of fact, most of the small series of photos he shoots in the Ivory Coast, is good for the trash can because of a badly placed film. Moreover, during his stay on the « black continent » he catches malaria, making people even fear for his life. After a fierce struggle, however, he comes back on top. |

|||

FIG.5 Three boys in Lake Tanganyika, M. Munkácsi Congo, 1930 |

|||

|

Seemingly awakened by the recent confrontation with the grim reaper, once back in Paris, his attention is drawn to a picture from the Hungarian press and fashion photographer Martin Munkácsi (1956 – 1963) in which three Congolese boys are running into a lake, cheering (FIG.5). Cartier-Bresson is baffled by the fact that this liveliness could be recorded by a camera. Later, he expresses his admiration for the work of Munkácsi in a letter to his daughter Joan. It is this ultimate impetus which convinces him to choose for photography as a means of expression. It is a choice that marks the beginning of Cartier-Bresson's successful career. A choice that will change the essence of press photography. When Cartier-Bresson indulges in photography at the beginning of the 1930s, he is also in no small measure influenced by André Kertész (1954 – 1985), one of the many respected photographers Hungary brought forth during the interwar period. Cartier-Bresson once summarized the innovative role of Kertész as: "Whatever we have done, Kertész did first!" Although Kertész is especially known for his still lifes, a part of his oeuvre is characterized by the same poignancy that can be seen throughout the work of Cartier-Bresson (FIG.6). |

|||

“En 1931 ou en 1932, j'ai eu l'occasion de voir une photo de ton père où trois enfants noirs courent vers la mer. Je dois dire que c'est cette photo qui comme une étincelle m'a embrasé. J'ai soudain compris que la photographie peut fixer l'éternité dans un instant. C'est la seule photo qui m'ait influencé. Il y a dans cette image une telle intensité, une telle spontanéité, une telle joie de vivre, une telle merveille qu'elle m'éblouit encore aujourd'hui.”Henri Cartier-Bresson

|

|||

|

The reading of a book of Schopenhauer makes him discover oriental philosophy. Later, Henri Cartier-Bresson states that his vision of the world was, in retrospect, in very good agreement with that of Buddhism. Despite his upbringing, he never really was a convicted Christian. When Martine Franck (1938 – 2012), his second wife, presents him to the Dalai Lama, she calls him "a confused Buddhist". This is evident from the involvement Cartier-Bresson approaches his subjects with, and the efforts he does not to act as a voyeur. Nevertheless, he has an aversion to the indifference and nonchalance which floods the world up until today. It surely is no coincidence that, in 1954, Cartier-Bresson is the first foreign photographer who is allowed into the Soviet Union, considering his subtle and respectful work ethic. Thought provoking is the fact that in 1948 he manages to take pictures of Gandhi, barely half an hour before his death, in his considerate and quiescent fashion. A collegue who rushes in at the same time is forced to hand in her photos immediately. Moreover, the legend tells us that Cartier-Bresson sometimes obscured his silver camera with tape or a handkerchief, in order to flutter even more inconspicuously through the masses. |

|||

FIG.6 Wandering violinist, A. Kertész Abony, Hungary, 1921 |

|||

|

Initially, Cartier-Bresson photographed with a Kodak Box Brownie, but once he purchases a sturdy Leica in Marseille around 1931, he swears by the quality and simplicity of this German company for the rest of his life. He considers this camera — one of the first compact cameras on the market, wchich makes it quiet, lightweight, unobtrusive and easy to handle — as an extension of his eye. He photographs, therefore, usually with a 50mm lens, which corresponds to the focal length of the human eye. Cartier-Bresson deliberately coldshoulders the emergence of the first easy-to-use color films, around 1935. He prefers the more evocative and expressive style of black and white photography. (He did a few assignments in color though, but since he destroyed most of the color negatives afterwards, his legacy is almost entirely monochrome. Some of his color series were published in Life during the 1950s and have been made available online by Time Magazine.) Unlike many other professional photographers, he also continues to work with 35mm film. Over the years, this format became the consumer's standard thanks to their great flexibility. The photographer does not need to insert a new negative after each shot in a cumbersome way, which comes in handy for a street reporter like Cartier-Bresson. { Printer-friendly version } { Read on: The Early Years (1931 – 1935) } |

|||

|

Le Couperet HCB © Frederik Neirynck 2004 – 2024

|

|||